Germany’s Election: What it means for Germany and Europe

The German federal election will take place on Sep. 26th. This is the first such election in 16 years that won’t have Angela Merkel on the ballot. It will elect a new leader for Germany and in effect a new leader for the European Union. Will German policies change dramatically after 16 years under Merkel? As Germany is the pivotal economy in Europe, accounting for nearly 30% of Eurozone GDP, its future strongly influences the continent and the currency. In this piece I’d like to explore the likely winner(s) of the election and what they might mean for Europe and the world at large.

First off, what are the main issues facing Germany in this election, the issues that the parties differ on? The major ones are:

Immigration: A common refugee policy is the #1 concern for European policy among voters. Germany absorbs the largest number of refugees of any EU country. Most parties are in favor of sharing this burden more evenly among the member countries. On other aspects of refugee policy though there’s a clear left/right divide: left-wing parties emphasize the right to claim asylum while right-wing parties emphasize strong border control.

Climate change: The recent floods in Germany have brought home the importance of this issue for everyone’s day-to-day life. Under its Fit for 55 package, the EU has set itself a binding target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. This requires current greenhouse gas emission levels to drop substantially in the next decades. How to achieve this goal is a major topic for debate among the parties. It’s tied to the question of fiscal policy because fighting climate change requires investment, which requires borrowing and/or higher taxes.

COVID-19 restrictions: There are some differences among the parties on the strategy of lockdowns and vaccinations.

Old-age pension: As the population ages, the national pension fund is running out of money. Some parties want to raise the retirement age, some want to increase the role of private pensions, some want to increase immigration to rectify the population imbalance.

EU integration: The EU Commission’s EUR 750bn Next Generation EU (NGEU) fund broke precedent by issuing bonds that were the liability of the EU as a whole, rather than just one country. Is this fund to be a “one-off” or is it a model for further financial integration of the EU? Should the EU Commission have its own financial resources? These are key questions for Europe’s future.

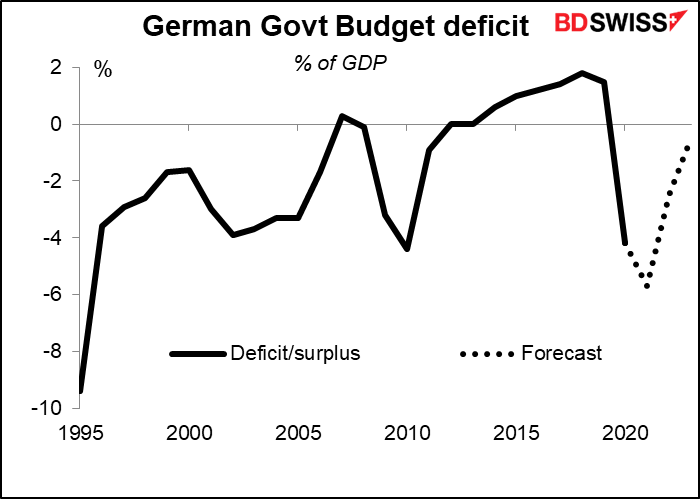

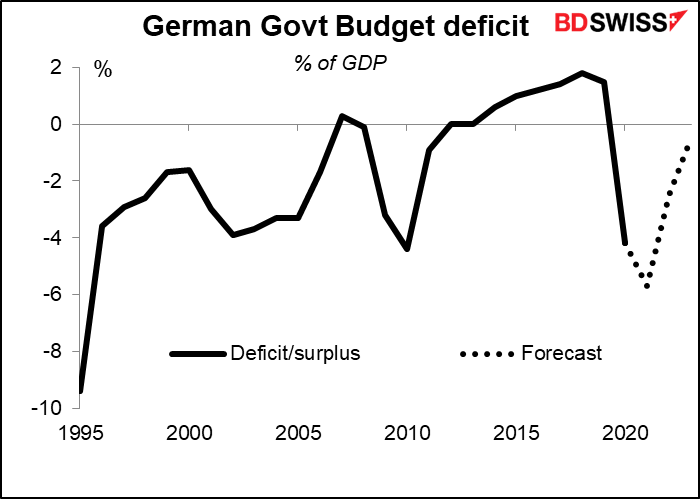

Domestic fiscal policy and the “debt brake:” The German constitution limits annual federal government borrowing (adjusted for the economic cycle) to no more than 0.35% of GDP. This clause, known as the “debt brake,” is currently suspended until 2023 because of the pandemic. Should the suspension be extended, should the “brake” be loosened, or should it be reinstated on schedule? This will have important consequences for the German and therefore EU economy.

The “Agenda 2010” reforms: There has been consistent pressure from the left to soften some of the 2003/05 labor market & social reforms known as the “Agenda 2010” package. The winning coalition might decide to make some changes here.

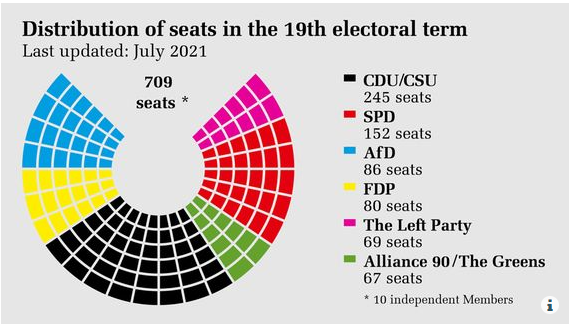

There will be six political parties contesting the election. Germany’s electoral system makes it difficult for any one party to form a government on its own, meaning that coalition governments tend to be the rule. The key to predicting the election then is to predict which parties are likely to form a coalition.

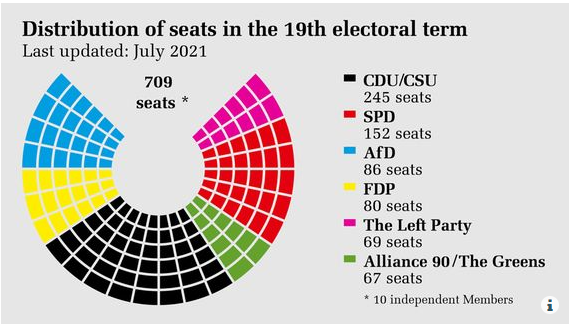

CDU/CSU: The largest party is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Socialist Union (CSU). It currently holds 245 seats in the 709-seat Bundestag. The CDU/CSU has led coalition governments under Merkel for nearly 16 years. The leaders of the two parties are Armin Laschet and Markus Soder, respectively. Laschet is the joint party’s candidate for Chancellor.

CDU/CSU: The largest party is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Socialist Union (CSU). It currently holds 245 seats in the 709-seat Bundestag. The CDU/CSU has led coalition governments under Merkel for nearly 16 years. The leaders of the two parties are Armin Laschet and Markus Soder, respectively. Laschet is the joint party’s candidate for Chancellor.

The CDU/CSU is considered to be “center-right,” although what is considered “right” in Europe would be considered nearly communist in the US. Laschet ran as the “continuity candidate” – Merkel in a business suit. He stands for continuity, fiscal conservatism, and modest changes to make Germany a bit more dynamic, greener, more digital. Thus it’s unlikely there would be any major changes in policy if he gets in.

SPD: The Social Democratic Party (SPD) is the second-largest party, with 152 seats. It’s described as “center-left.” As the #2 party, it’s been the smaller member of the “Grand Coalition” government with the CDU/CSU since 2013. Its candidate for Chancellor is Olaf Scholz, the current Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister. The party is strongly pro-EU and believes in further integration and shared responsibility across the EU. This has meant that its membership in the coalition has forced it to compromise a lot, since the CDU/CSU disagrees on these points. The SDP has caused the CDU/CSU to soften some of the “Agenda 2010”

AfD: Alternative for Germany (AfD) is the third-largest party with 86 seats, but they don’t matter. They’re a right-wing populist political party known for their opposition to the EU and immigration. The reason they don’t matter is that all the other parties have pledged not to enter into a coalition with them. Unless there was some stunning result that meant no government could be formed without them, they’re out of the picture.

FDP: The Free Democratic Party (FDP), with 80 seats, is the libertarian party and the party of business. It advocates lower taxes, more civil liberties, and cutting back the welfare state, including furthering the “Agenda 2010” reforms. It believes in laissez-faire and free markets. Its proposals include a cut in the corporation tax. It takes a relatively strict line on immigration (favoring a Canada-style points system) and is cautious about EU integration – it wants a European constitution and European army but objects to fiscal risk-sharing.

The Left: The Left was founded in 2007 through the merger of the Party of Democratic Socialism and Labour and Social Justice-The Electoral Alternative. It currently has 69 seats in the Bundestag, making it the 5th largest party. It’s never been part of a coalition federal government although it is a junior partner in some local governments. Its positions can easily be deduced from its name. It favors large-scale investment in public services and infrastructure, which it would fund by hiking income and corporation taxes. It also favors leaving NATO. The Left is most opposed to the “Agenda 2010” reforms.

The Greens: With only 67 seats at the moment, the smallest group in the Bundestag, this ecology-minded party might not seem that important, but many of the calculations about possible coalitions require the Greens to make them work. Furthermore, the party appears to be on course to achieve its best-ever result this time under the co-leadership of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck. Ms. Baerbock is the party’s candidate for Chancellor. The Greens’ main goal is for the economy to be greenhouse gas-neutral within at least 20 years. Its green policies include such extensive measures as expanding the rail network and requiring greater energy efficiency in homes. This would require substantial government investment, which would probably necessitate a hike in income tax for the highest earners and a “reform” of the debt brake. The Greens are also in favor of softening or reversing some of the “Agenda 2010” reforms.

Overall we shouldn’t exaggerate the differences between the parties. In many aspects they are more differences of emphasis. They mostly agree on the need to “go green,” with of course the Green Party putting the most emphasis on this policy. The differences largely are on how to fund the necessary changes. All parties agree on the need to invest in a more digital future while upgrading the health system. On the European level, all the major parties want to strengthen European integration, just in different ways, especially with regards to fiscal integration and which national government roles should be turned over to the supranational level.

Where do we stand?

The polls show the CDU/CSU well ahead, but with the Greens, rather than the SPD, in second place. As usual, no party is likely to be in a position to govern by itself. The focus therefore is on what parties might form a coalition and how the need to compromise in a coalition might affect their policies.

The possible coalition combinations are often referred to by the pattern that their colors would make.

Currently the only two-party coalition possible seems to be the CDU/CSU and the Greens (the so-called “black/green” coalition). This is the most likely outcome of the election at the moment. These two parties have similar views on infrastructure investment, social policies, and climate change, although the Greens are more aggressive on the latter issue. However, they have serious differences on fiscal and EU policy. The CDU/CSU doesn’t want any tax hikes and wants to keep the debt brake and balanced budget target, while it rejects the idea of an EU debt union and wants to keep the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules limiting countries’ budget deficits. The Greens on the other hand want a wealth tax, higher taxes for the top income earners, want to make the debt brake more flexible, and support a common EU fiscal policy and reform of the SGP. This is one of the main areas of difference that’s important to the euro.

Currently the only two-party coalition possible seems to be the CDU/CSU and the Greens (the so-called “black/green” coalition). This is the most likely outcome of the election at the moment. These two parties have similar views on infrastructure investment, social policies, and climate change, although the Greens are more aggressive on the latter issue. However, they have serious differences on fiscal and EU policy. The CDU/CSU doesn’t want any tax hikes and wants to keep the debt brake and balanced budget target, while it rejects the idea of an EU debt union and wants to keep the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules limiting countries’ budget deficits. The Greens on the other hand want a wealth tax, higher taxes for the top income earners, want to make the debt brake more flexible, and support a common EU fiscal policy and reform of the SGP. This is one of the main areas of difference that’s important to the euro.

The significant differences between the two parties on fiscal policy mean that there would have to be lengthy negotiations and some compromises before they could reach agreement. Assuming though that the CDU/CSU is the senior party and retains the Chancellorship, I would not expect any major changes, although there could be a softer fiscal stance to accommodate the Greens’ investment goals.

Three-party coalitions

The key question is whether there could be a three-party coalition without the CDU/CSU. If the CDU/CSU is in a three-way coalition, it will be the largest party and therefore will naturally control the platform, albeit with some compromises to its junior partners. Major policy changes are only likely in a coalition that does not include the CDU/CSU.

Mathematically there are any number of three-party coalitions possible, but some are difficult to imagine coming about in real life. EG the policies of the Left and the FDP are too far apart to imagine shoehorning them into a coalition together. It could even be difficult for the SPD and the FDP to work out a common platform.

The most likely three-party coalition is the CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP (the “Jamaica” coalition, after the colors in that country’s flag).

The FDP’s policies have more in common with those of the CDU/CSU than with the Greens. Adding it to the coalition would strengthen the CDU’s hand in negotiations and probably result in a more right-wing, free-market economy with limits to borrowing. This could be the market’s favorite combination.

CDU/CSU + Greens + SPD (Black/Green/Red) (the “Kenya” coalition, after that country’s flag). The SDP’s position on German and EU fiscal policy is similar to that of the Greens. This combination would therefore be the opposite of the previous one in that the SPD would tend to strengthen the Greens’ hand in the negotiations, rather than the FDP strengthening the CDUs.

The polls suggest that this combination would have the largest number of seats in the Bundestag. Nonetheless it’s less likely, because the center-right CDU/CSU would rather not ally itself with two center-left parties that have such different priorities. Moreover, the SPD’s popularity has fallen since the last election and may see an opportunity to rebuild its fortunes as the main opposition party.

Greens + SPD Left: the risk scenario These three left-wing parties have no major differences on the broad issues, just matters of emphasis, timing, and amounts. They would represent a major change in German policy. They would probably try to amend the debt brake, which could set up a conflict with EU rules. They would also want to increase social spending and impose tighter regulations of labor, service and housing markets. However, this coalition has major problems because the pro-Putin and anti-NATO stance of the Left Party is in contradiction to the Geens’ hard line against Russia and China on human rights abuses.

The likelihood of this coalition coming into power is low. However as long as it’s not impossible, it will be a risk for the euro.

There is also talk of the “traffic light” coalition of Greens + FDP + SPD, but again, fitting the right-wing FDP in with these two left-wing parties seems impossible unless they are all so eager to get into office without the CDU/CSU that some of the parties abandon many of their key principles.

The timeline: All the major parties have presented their manifestos. Serious campaigning usually gets underway in late August after the summer holidays end. After the election on Sep 26th, coalition negotiations usually take four to eight weeks, during which period the former government remains in office. The new parliament is scheduled to convene on Nov. 8th.

Market implications: it depends

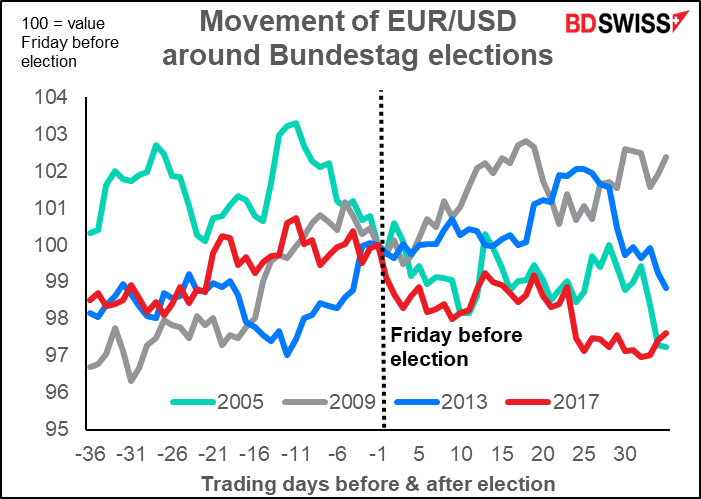

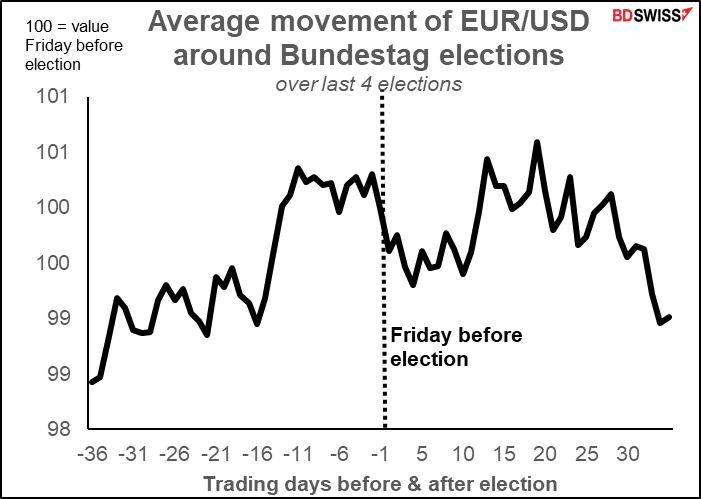

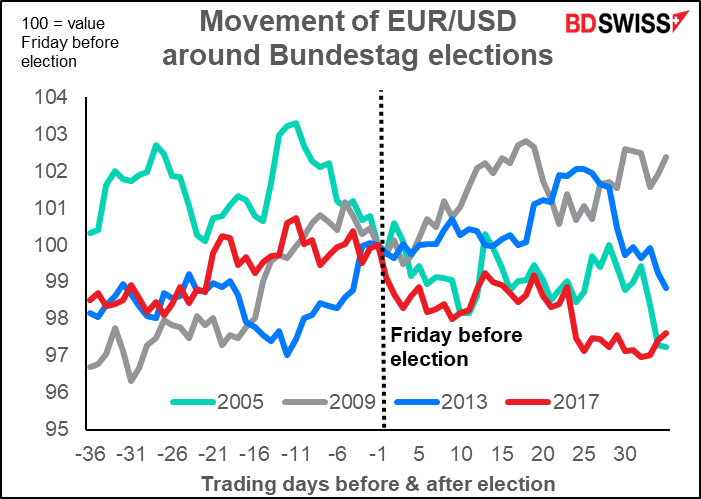

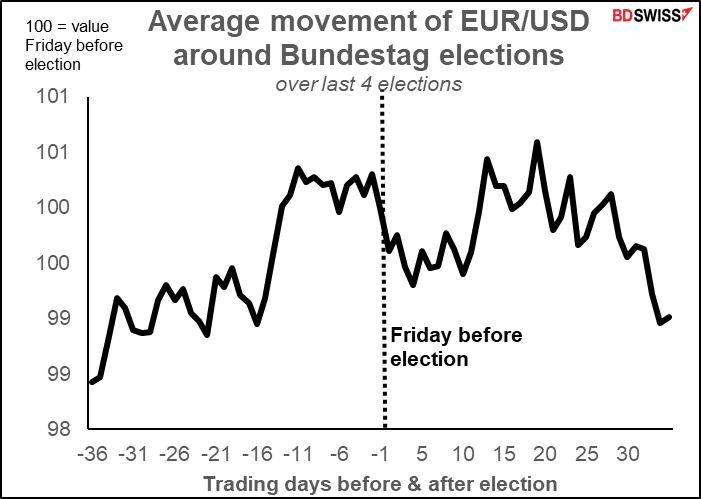

Bundestag elections are held around the same time in September. If we look at how EUR/USD behaved from the beginning of August until a mid-November, we see that in general EUR/USD has risen (i.e. EUR has strengthened) going into the election, then weakened immediately after. This probably reflects a typical “buy the rumor, sell the fact” reaction: investors buying EUR in anticipation that Merkel will win, then taking profits after she does.

This time around though there’s no Merkel on the ballot. Furthermore, the usual rules of thumb about currencies may be turned on their heads now. Generally speaking, market participants tend to be right-wing and prefer right-wing outcomes, eg the Republicans in the US (even though the US economy, stock market and the dollar have historically performed better under Democrats. But who said markets are rational?)

This time around though there’s no Merkel on the ballot. Furthermore, the usual rules of thumb about currencies may be turned on their heads now. Generally speaking, market participants tend to be right-wing and prefer right-wing outcomes, eg the Republicans in the US (even though the US economy, stock market and the dollar have historically performed better under Democrats. But who said markets are rational?)

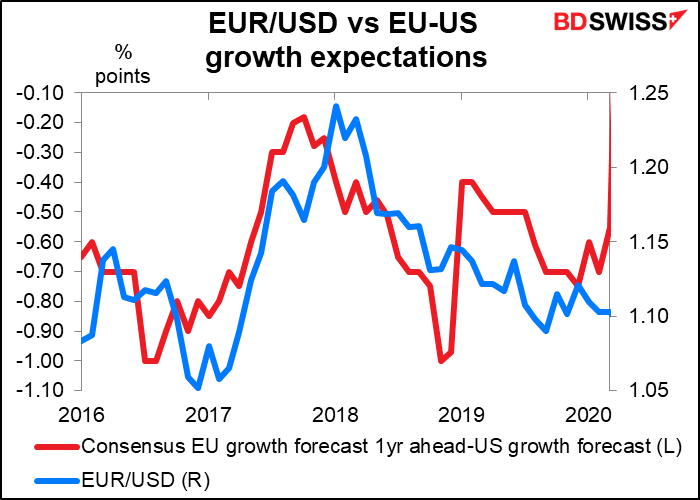

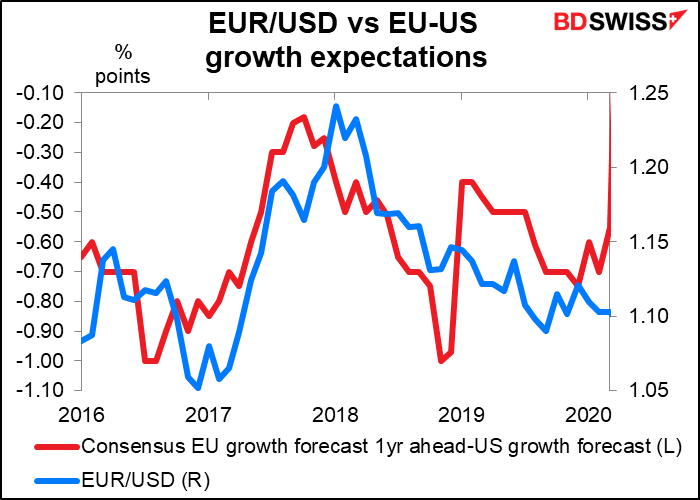

In this case too, one might think that the “Jamaica” coalition, with the FDP bolstering the CDU/CSU’s right-wing views, would be the market’s favorite. However, nowadays investors are looking for growth, not fiscal rectitude. Out-of-control borrowing & spending is simply not on the agenda in Germany in any case, whereas painful austerity and contraction could be if the CDU/CSU team up with the FDP. I believe a CDU/CSU + Greens coalition would be better for EUR than CDU/CUS + Greens + FDP. Hopes of faster growth could attract money into European stocks, while if the left-leaning coalition meant higher Bund yields, that too could make the EUR more attractive.

At the moment, US fiscal policy is making a bigger contribution to growth there than EU fiscal policy is, but in coming years as the US winds down its extraordinary policies and the EU’s NGEU fund continues to disburse funds, the EU’s fiscal contraction should be less acute than the US’. That may be one factor supporting EUR/USD. If however Germany goes back to plowing the furrow of Teutonic rectitude, EU growth could slow and EUR/USD move still lower.

At the moment, US fiscal policy is making a bigger contribution to growth there than EU fiscal policy is, but in coming years as the US winds down its extraordinary policies and the EU’s NGEU fund continues to disburse funds, the EU’s fiscal contraction should be less acute than the US’. That may be one factor supporting EUR/USD. If however Germany goes back to plowing the furrow of Teutonic rectitude, EU growth could slow and EUR/USD move still lower.

Either way, the FX market doesn’t seem to be that concerned about the election. If it were, then the risk reversals would show some movement as they come to cover the period of the election – eg the 4-month risk reversal would either rise or fall as soon as it came to be four months before the election. But we see no such movement in the riskies, leading me to think that investors aren’t that worried about the implications of the election for the currency. That may be because of domestic constraints built into the German political system that stymie any sudden major changes.

Either way, the FX market doesn’t seem to be that concerned about the election. If it were, then the risk reversals would show some movement as they come to cover the period of the election – eg the 4-month risk reversal would either rise or fall as soon as it came to be four months before the election. But we see no such movement in the riskies, leading me to think that investors aren’t that worried about the implications of the election for the currency. That may be because of domestic constraints built into the German political system that stymie any sudden major changes.

By contrast, we’ve already seen moves in the risk reversals in conjunction with the French elections in 2022, which will start on April 10th next year. The one-year risk reversal fell sharply (i.e., demand for EUR/USD puts increase) as soon as it encompassed the first round of voting and the 9m RR also fall as soon as it encompassed that date.

By contrast, we’ve already seen moves in the risk reversals in conjunction with the French elections in 2022, which will start on April 10th next year. The one-year risk reversal fell sharply (i.e., demand for EUR/USD puts increase) as soon as it encompassed the first round of voting and the 9m RR also fall as soon as it encompassed that date.

No big change in any case

No big change in any case

The focus of international investors is on the scope for a major change in Germany’s domestic fiscal policy toward a more expansive stance and more risk-sharing in Europe. Although the parties do differ on these matters, there is a limit to how much change they can implement. Due to the limits set in the German constitution, the oversight of the constitutional court, and the role of the Bundesrat, the scope for large-scale shifts in the overall stance of fiscal policy and of German guarantees for EU-wide borrowing is limited regardless of who gets into power.

No matter who wins, change will only come slowly to Germany and the EU. The new Chancellor will not have the long history and authority of Merkel and will have to focus on building a consensus within the coalition rather than taking any bold new moves.

Furthermore, German politics works largely by consensus, rather than the “elected dictatorship” of a country like Britain or France. Major shifts in policy are usually negotiated and agreed upon between the mainstream parties, both in the ruling coalition and in opposition. Such shifts usually reflect longer processes, not sudden policy reversals when a new government gets in. Part of that is cultural; part is because of the need for a coalition government, which usually ensures some continuity between governments.

Part is also due to the need for both houses of parliament to pass legislation, which often gives the mainstream opposition a veto in the Bundesrat (see below). EG the Greens have not been a member of the current coalition at the federal level, but they have exerted influence on the legislative agenda through their veto power in the Bundesrat. Similarly, if the Greens replace the SPD in the next coalition, then the SPD could play that role. Crucially, any coalition without the CDU/CSU would still have to deal with a CDU/CSU veto in the Bundesrat, which would significantly restrict the new government’s room to make major changes in fiscal and European policies.

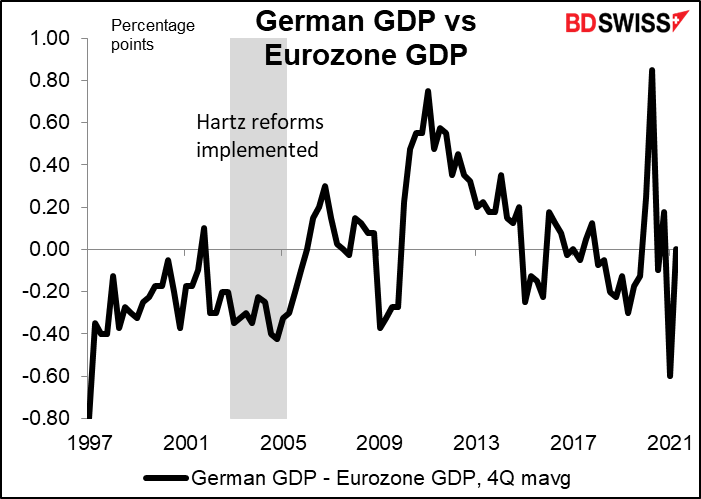

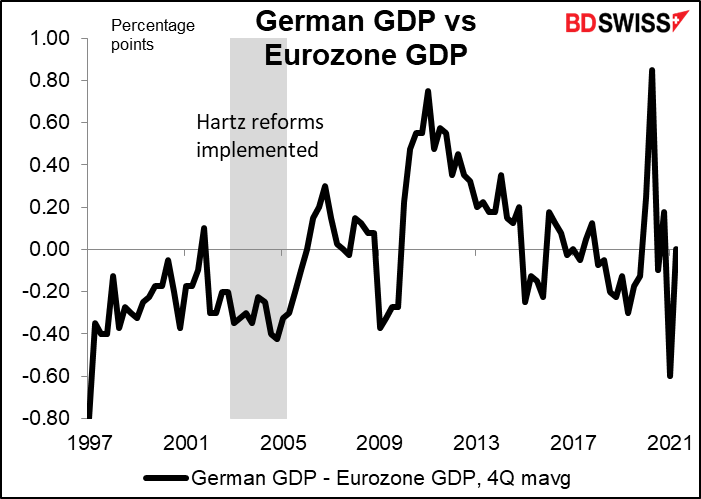

Perhaps the most important question is not the near-term fiscal policy or policy toward EU integration, but rather the policy toward the sweeping labor market and welfare reform package known as “Agenda 2010” that launched Germany’s “golden decade.” It’s hard to remember now, but in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Germany was often called "the sick man of Europe." Growth averaged only about 1.2% a year 1998 to 2005, including a recession in 2003, and unemployment rates rose from 9.2% in 1998 to 11.1%. It was the Hartz reforms to the labor market, enacted between 2003 to 2005, plus other changes made as part of the “Agenda 2010” around that time that eventually turned Germany from the “sick man” of Europe into the “locomotive of growth” of the continent.

Perhaps the most important question is not the near-term fiscal policy or policy toward EU integration, but rather the policy toward the sweeping labor market and welfare reform package known as “Agenda 2010” that launched Germany’s “golden decade.” It’s hard to remember now, but in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Germany was often called "the sick man of Europe." Growth averaged only about 1.2% a year 1998 to 2005, including a recession in 2003, and unemployment rates rose from 9.2% in 1998 to 11.1%. It was the Hartz reforms to the labor market, enacted between 2003 to 2005, plus other changes made as part of the “Agenda 2010” around that time that eventually turned Germany from the “sick man” of Europe into the “locomotive of growth” of the continent.

Growth went from below the EU average to above…

…while unemployment went from above the EU average to below.

…while unemployment went from above the EU average to below.

As long as the CDU/CSU is in the coalition, these reforms are likely to be intact. They could even be enhanced if the FDP joins the coalition. However, a swing left in the government – e.g the “black/green/red” coalition of CDU/CSU with the Greens and the SPD, which have been the source of much of the pressure to ease up on the reforms, could put more burdens on employers that drive jobs abroad and lower Germany’s growth rate.

For more information: The German news channel DW has an extremely useful website on the German elections in which they discuss the issues and the players in English. Deutsche Bank also makes much of its research on Germany available on its website.

The German political system explained (briefly)

The Bundestag (“Federal Diet”) is the most important part of the legislative branch of the German federation. Together with the Bundesrat (see below), it comprises the legislative branch of the federal government. It passes laws, decides on the federal budget, exercises oversight of the executive branch, and decides on foreign activity by the armed forces.

It elects a Chancellor, who is responsible for forming a government by proposing candidates for the federal cabinet and determining policy guidelines (see below).

Electoral system: The electoral system is extraordinarily complicated. It’s a mixed-member proportional representation system.

Every elector has two votes: a constituency vote (first vote) and a party list vote (second vote). The first votes elect 299 members in single-member constituencies. This is done by first-past-the-post voting, i.e. the candidate who gets the most votes wins even if they don’t get a majority. The second votes are then used to allocate a proportionate number of seats to the parties. These are allocated first in the states and then on the federal level. There are then a whole lot of complicated ways in which the seats are reapportioned depending on whether each party wins fewer or more constituency seats in a state that its second votes would entitle it to. Anyone wanting more detail than that is welcome to read about it on Wikipedia. I wish you good luck.

Role of the chancellor: The chancellor is the head of government and the chief executive of Germany. The chancellor can appoint and dismiss members of the cabinet at will (technically the president does it on the recommendation of the chancellor). Article 65 of the Basic Law says “The Federal Chancellor shall determine and be responsible for the general guidelines of policy.” Chancellors have used this rule to take control over the cabinet, treating cabinet members as subordinates whose job it is to implement the chancellor’s views and making the chancellor the clear focus of power in Germany.

The Bundesrat (“Federal Council”) s the body that represents the country’s 16 Lander (states) at the federal level. The main difference from the Bundestag is that the representatives are appointed by the state governments, rather than being elected directly by the people. It has only 69 members and normally has one session a month to vote on legislation prepared in committee. Its main purpose is to defend the interests of the Lander with respect to the federal government and, indirectly, the EU. The legislative authority of the Bundesrat is subordinate to that of the Bundestag but still essential. The federal government must present all its legislative initiatives first to the Bundesrat; only thereafter can a proposal be passed to the Bundestag.

Constitutional changes require the approval of the majority of two-thirds of all votes in Bundestag and Bundesrat. This gives the Bundesrat an absolute veto against constitutional change. For other legislation the Bundesrat can use a conditional veto that the Bundestag can overrule if it has enough votes (50%+1 in some cases, two-thirds in others), or an absolute veto that requires a joint committee to work out a compromise.

The state governments are required to vote en bloc in the Bundesrat. If a state’s delegation can’t agree on how to vote, they abstain. This automatically counts as a “no” vote. If the opposition parties have enough representation in enough states, it enables them to veto legislation this way.

First off, what are the main issues facing Germany in this election, the issues that the parties differ on? The major ones are:

Immigration: A common refugee policy is the #1 concern for European policy among voters. Germany absorbs the largest number of refugees of any EU country. Most parties are in favor of sharing this burden more evenly among the member countries. On other aspects of refugee policy though there’s a clear left/right divide: left-wing parties emphasize the right to claim asylum while right-wing parties emphasize strong border control.

Climate change: The recent floods in Germany have brought home the importance of this issue for everyone’s day-to-day life. Under its Fit for 55 package, the EU has set itself a binding target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. This requires current greenhouse gas emission levels to drop substantially in the next decades. How to achieve this goal is a major topic for debate among the parties. It’s tied to the question of fiscal policy because fighting climate change requires investment, which requires borrowing and/or higher taxes.

COVID-19 restrictions: There are some differences among the parties on the strategy of lockdowns and vaccinations.

Old-age pension: As the population ages, the national pension fund is running out of money. Some parties want to raise the retirement age, some want to increase the role of private pensions, some want to increase immigration to rectify the population imbalance.

EU integration: The EU Commission’s EUR 750bn Next Generation EU (NGEU) fund broke precedent by issuing bonds that were the liability of the EU as a whole, rather than just one country. Is this fund to be a “one-off” or is it a model for further financial integration of the EU? Should the EU Commission have its own financial resources? These are key questions for Europe’s future.

Domestic fiscal policy and the “debt brake:” The German constitution limits annual federal government borrowing (adjusted for the economic cycle) to no more than 0.35% of GDP. This clause, known as the “debt brake,” is currently suspended until 2023 because of the pandemic. Should the suspension be extended, should the “brake” be loosened, or should it be reinstated on schedule? This will have important consequences for the German and therefore EU economy.

The “Agenda 2010” reforms: There has been consistent pressure from the left to soften some of the 2003/05 labor market & social reforms known as the “Agenda 2010” package. The winning coalition might decide to make some changes here.

There will be six political parties contesting the election. Germany’s electoral system makes it difficult for any one party to form a government on its own, meaning that coalition governments tend to be the rule. The key to predicting the election then is to predict which parties are likely to form a coalition.

CDU/CSU: The largest party is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Socialist Union (CSU). It currently holds 245 seats in the 709-seat Bundestag. The CDU/CSU has led coalition governments under Merkel for nearly 16 years. The leaders of the two parties are Armin Laschet and Markus Soder, respectively. Laschet is the joint party’s candidate for Chancellor.

CDU/CSU: The largest party is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Socialist Union (CSU). It currently holds 245 seats in the 709-seat Bundestag. The CDU/CSU has led coalition governments under Merkel for nearly 16 years. The leaders of the two parties are Armin Laschet and Markus Soder, respectively. Laschet is the joint party’s candidate for Chancellor.The CDU/CSU is considered to be “center-right,” although what is considered “right” in Europe would be considered nearly communist in the US. Laschet ran as the “continuity candidate” – Merkel in a business suit. He stands for continuity, fiscal conservatism, and modest changes to make Germany a bit more dynamic, greener, more digital. Thus it’s unlikely there would be any major changes in policy if he gets in.

SPD: The Social Democratic Party (SPD) is the second-largest party, with 152 seats. It’s described as “center-left.” As the #2 party, it’s been the smaller member of the “Grand Coalition” government with the CDU/CSU since 2013. Its candidate for Chancellor is Olaf Scholz, the current Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister. The party is strongly pro-EU and believes in further integration and shared responsibility across the EU. This has meant that its membership in the coalition has forced it to compromise a lot, since the CDU/CSU disagrees on these points. The SDP has caused the CDU/CSU to soften some of the “Agenda 2010”

AfD: Alternative for Germany (AfD) is the third-largest party with 86 seats, but they don’t matter. They’re a right-wing populist political party known for their opposition to the EU and immigration. The reason they don’t matter is that all the other parties have pledged not to enter into a coalition with them. Unless there was some stunning result that meant no government could be formed without them, they’re out of the picture.

FDP: The Free Democratic Party (FDP), with 80 seats, is the libertarian party and the party of business. It advocates lower taxes, more civil liberties, and cutting back the welfare state, including furthering the “Agenda 2010” reforms. It believes in laissez-faire and free markets. Its proposals include a cut in the corporation tax. It takes a relatively strict line on immigration (favoring a Canada-style points system) and is cautious about EU integration – it wants a European constitution and European army but objects to fiscal risk-sharing.

The Left: The Left was founded in 2007 through the merger of the Party of Democratic Socialism and Labour and Social Justice-The Electoral Alternative. It currently has 69 seats in the Bundestag, making it the 5th largest party. It’s never been part of a coalition federal government although it is a junior partner in some local governments. Its positions can easily be deduced from its name. It favors large-scale investment in public services and infrastructure, which it would fund by hiking income and corporation taxes. It also favors leaving NATO. The Left is most opposed to the “Agenda 2010” reforms.

The Greens: With only 67 seats at the moment, the smallest group in the Bundestag, this ecology-minded party might not seem that important, but many of the calculations about possible coalitions require the Greens to make them work. Furthermore, the party appears to be on course to achieve its best-ever result this time under the co-leadership of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck. Ms. Baerbock is the party’s candidate for Chancellor. The Greens’ main goal is for the economy to be greenhouse gas-neutral within at least 20 years. Its green policies include such extensive measures as expanding the rail network and requiring greater energy efficiency in homes. This would require substantial government investment, which would probably necessitate a hike in income tax for the highest earners and a “reform” of the debt brake. The Greens are also in favor of softening or reversing some of the “Agenda 2010” reforms.

Overall we shouldn’t exaggerate the differences between the parties. In many aspects they are more differences of emphasis. They mostly agree on the need to “go green,” with of course the Green Party putting the most emphasis on this policy. The differences largely are on how to fund the necessary changes. All parties agree on the need to invest in a more digital future while upgrading the health system. On the European level, all the major parties want to strengthen European integration, just in different ways, especially with regards to fiscal integration and which national government roles should be turned over to the supranational level.

Where do we stand?

The polls show the CDU/CSU well ahead, but with the Greens, rather than the SPD, in second place. As usual, no party is likely to be in a position to govern by itself. The focus therefore is on what parties might form a coalition and how the need to compromise in a coalition might affect their policies.

The possible coalition combinations are often referred to by the pattern that their colors would make.

Currently the only two-party coalition possible seems to be the CDU/CSU and the Greens (the so-called “black/green” coalition). This is the most likely outcome of the election at the moment. These two parties have similar views on infrastructure investment, social policies, and climate change, although the Greens are more aggressive on the latter issue. However, they have serious differences on fiscal and EU policy. The CDU/CSU doesn’t want any tax hikes and wants to keep the debt brake and balanced budget target, while it rejects the idea of an EU debt union and wants to keep the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules limiting countries’ budget deficits. The Greens on the other hand want a wealth tax, higher taxes for the top income earners, want to make the debt brake more flexible, and support a common EU fiscal policy and reform of the SGP. This is one of the main areas of difference that’s important to the euro.

Currently the only two-party coalition possible seems to be the CDU/CSU and the Greens (the so-called “black/green” coalition). This is the most likely outcome of the election at the moment. These two parties have similar views on infrastructure investment, social policies, and climate change, although the Greens are more aggressive on the latter issue. However, they have serious differences on fiscal and EU policy. The CDU/CSU doesn’t want any tax hikes and wants to keep the debt brake and balanced budget target, while it rejects the idea of an EU debt union and wants to keep the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules limiting countries’ budget deficits. The Greens on the other hand want a wealth tax, higher taxes for the top income earners, want to make the debt brake more flexible, and support a common EU fiscal policy and reform of the SGP. This is one of the main areas of difference that’s important to the euro. The significant differences between the two parties on fiscal policy mean that there would have to be lengthy negotiations and some compromises before they could reach agreement. Assuming though that the CDU/CSU is the senior party and retains the Chancellorship, I would not expect any major changes, although there could be a softer fiscal stance to accommodate the Greens’ investment goals.

Three-party coalitions

The key question is whether there could be a three-party coalition without the CDU/CSU. If the CDU/CSU is in a three-way coalition, it will be the largest party and therefore will naturally control the platform, albeit with some compromises to its junior partners. Major policy changes are only likely in a coalition that does not include the CDU/CSU.

Mathematically there are any number of three-party coalitions possible, but some are difficult to imagine coming about in real life. EG the policies of the Left and the FDP are too far apart to imagine shoehorning them into a coalition together. It could even be difficult for the SPD and the FDP to work out a common platform.

The most likely three-party coalition is the CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP (the “Jamaica” coalition, after the colors in that country’s flag).

The FDP’s policies have more in common with those of the CDU/CSU than with the Greens. Adding it to the coalition would strengthen the CDU’s hand in negotiations and probably result in a more right-wing, free-market economy with limits to borrowing. This could be the market’s favorite combination.

CDU/CSU + Greens + SPD (Black/Green/Red) (the “Kenya” coalition, after that country’s flag). The SDP’s position on German and EU fiscal policy is similar to that of the Greens. This combination would therefore be the opposite of the previous one in that the SPD would tend to strengthen the Greens’ hand in the negotiations, rather than the FDP strengthening the CDUs.

The polls suggest that this combination would have the largest number of seats in the Bundestag. Nonetheless it’s less likely, because the center-right CDU/CSU would rather not ally itself with two center-left parties that have such different priorities. Moreover, the SPD’s popularity has fallen since the last election and may see an opportunity to rebuild its fortunes as the main opposition party.

Greens + SPD Left: the risk scenario These three left-wing parties have no major differences on the broad issues, just matters of emphasis, timing, and amounts. They would represent a major change in German policy. They would probably try to amend the debt brake, which could set up a conflict with EU rules. They would also want to increase social spending and impose tighter regulations of labor, service and housing markets. However, this coalition has major problems because the pro-Putin and anti-NATO stance of the Left Party is in contradiction to the Geens’ hard line against Russia and China on human rights abuses.

The likelihood of this coalition coming into power is low. However as long as it’s not impossible, it will be a risk for the euro.

There is also talk of the “traffic light” coalition of Greens + FDP + SPD, but again, fitting the right-wing FDP in with these two left-wing parties seems impossible unless they are all so eager to get into office without the CDU/CSU that some of the parties abandon many of their key principles.

The timeline: All the major parties have presented their manifestos. Serious campaigning usually gets underway in late August after the summer holidays end. After the election on Sep 26th, coalition negotiations usually take four to eight weeks, during which period the former government remains in office. The new parliament is scheduled to convene on Nov. 8th.

Market implications: it depends

Bundestag elections are held around the same time in September. If we look at how EUR/USD behaved from the beginning of August until a mid-November, we see that in general EUR/USD has risen (i.e. EUR has strengthened) going into the election, then weakened immediately after. This probably reflects a typical “buy the rumor, sell the fact” reaction: investors buying EUR in anticipation that Merkel will win, then taking profits after she does.

This time around though there’s no Merkel on the ballot. Furthermore, the usual rules of thumb about currencies may be turned on their heads now. Generally speaking, market participants tend to be right-wing and prefer right-wing outcomes, eg the Republicans in the US (even though the US economy, stock market and the dollar have historically performed better under Democrats. But who said markets are rational?)

This time around though there’s no Merkel on the ballot. Furthermore, the usual rules of thumb about currencies may be turned on their heads now. Generally speaking, market participants tend to be right-wing and prefer right-wing outcomes, eg the Republicans in the US (even though the US economy, stock market and the dollar have historically performed better under Democrats. But who said markets are rational?)In this case too, one might think that the “Jamaica” coalition, with the FDP bolstering the CDU/CSU’s right-wing views, would be the market’s favorite. However, nowadays investors are looking for growth, not fiscal rectitude. Out-of-control borrowing & spending is simply not on the agenda in Germany in any case, whereas painful austerity and contraction could be if the CDU/CSU team up with the FDP. I believe a CDU/CSU + Greens coalition would be better for EUR than CDU/CUS + Greens + FDP. Hopes of faster growth could attract money into European stocks, while if the left-leaning coalition meant higher Bund yields, that too could make the EUR more attractive.

At the moment, US fiscal policy is making a bigger contribution to growth there than EU fiscal policy is, but in coming years as the US winds down its extraordinary policies and the EU’s NGEU fund continues to disburse funds, the EU’s fiscal contraction should be less acute than the US’. That may be one factor supporting EUR/USD. If however Germany goes back to plowing the furrow of Teutonic rectitude, EU growth could slow and EUR/USD move still lower.

At the moment, US fiscal policy is making a bigger contribution to growth there than EU fiscal policy is, but in coming years as the US winds down its extraordinary policies and the EU’s NGEU fund continues to disburse funds, the EU’s fiscal contraction should be less acute than the US’. That may be one factor supporting EUR/USD. If however Germany goes back to plowing the furrow of Teutonic rectitude, EU growth could slow and EUR/USD move still lower. Either way, the FX market doesn’t seem to be that concerned about the election. If it were, then the risk reversals would show some movement as they come to cover the period of the election – eg the 4-month risk reversal would either rise or fall as soon as it came to be four months before the election. But we see no such movement in the riskies, leading me to think that investors aren’t that worried about the implications of the election for the currency. That may be because of domestic constraints built into the German political system that stymie any sudden major changes.

Either way, the FX market doesn’t seem to be that concerned about the election. If it were, then the risk reversals would show some movement as they come to cover the period of the election – eg the 4-month risk reversal would either rise or fall as soon as it came to be four months before the election. But we see no such movement in the riskies, leading me to think that investors aren’t that worried about the implications of the election for the currency. That may be because of domestic constraints built into the German political system that stymie any sudden major changes. By contrast, we’ve already seen moves in the risk reversals in conjunction with the French elections in 2022, which will start on April 10th next year. The one-year risk reversal fell sharply (i.e., demand for EUR/USD puts increase) as soon as it encompassed the first round of voting and the 9m RR also fall as soon as it encompassed that date.

By contrast, we’ve already seen moves in the risk reversals in conjunction with the French elections in 2022, which will start on April 10th next year. The one-year risk reversal fell sharply (i.e., demand for EUR/USD puts increase) as soon as it encompassed the first round of voting and the 9m RR also fall as soon as it encompassed that date.

No big change in any case

No big change in any caseThe focus of international investors is on the scope for a major change in Germany’s domestic fiscal policy toward a more expansive stance and more risk-sharing in Europe. Although the parties do differ on these matters, there is a limit to how much change they can implement. Due to the limits set in the German constitution, the oversight of the constitutional court, and the role of the Bundesrat, the scope for large-scale shifts in the overall stance of fiscal policy and of German guarantees for EU-wide borrowing is limited regardless of who gets into power.

No matter who wins, change will only come slowly to Germany and the EU. The new Chancellor will not have the long history and authority of Merkel and will have to focus on building a consensus within the coalition rather than taking any bold new moves.

Furthermore, German politics works largely by consensus, rather than the “elected dictatorship” of a country like Britain or France. Major shifts in policy are usually negotiated and agreed upon between the mainstream parties, both in the ruling coalition and in opposition. Such shifts usually reflect longer processes, not sudden policy reversals when a new government gets in. Part of that is cultural; part is because of the need for a coalition government, which usually ensures some continuity between governments.

Part is also due to the need for both houses of parliament to pass legislation, which often gives the mainstream opposition a veto in the Bundesrat (see below). EG the Greens have not been a member of the current coalition at the federal level, but they have exerted influence on the legislative agenda through their veto power in the Bundesrat. Similarly, if the Greens replace the SPD in the next coalition, then the SPD could play that role. Crucially, any coalition without the CDU/CSU would still have to deal with a CDU/CSU veto in the Bundesrat, which would significantly restrict the new government’s room to make major changes in fiscal and European policies.

Perhaps the most important question is not the near-term fiscal policy or policy toward EU integration, but rather the policy toward the sweeping labor market and welfare reform package known as “Agenda 2010” that launched Germany’s “golden decade.” It’s hard to remember now, but in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Germany was often called "the sick man of Europe." Growth averaged only about 1.2% a year 1998 to 2005, including a recession in 2003, and unemployment rates rose from 9.2% in 1998 to 11.1%. It was the Hartz reforms to the labor market, enacted between 2003 to 2005, plus other changes made as part of the “Agenda 2010” around that time that eventually turned Germany from the “sick man” of Europe into the “locomotive of growth” of the continent.

Perhaps the most important question is not the near-term fiscal policy or policy toward EU integration, but rather the policy toward the sweeping labor market and welfare reform package known as “Agenda 2010” that launched Germany’s “golden decade.” It’s hard to remember now, but in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, Germany was often called "the sick man of Europe." Growth averaged only about 1.2% a year 1998 to 2005, including a recession in 2003, and unemployment rates rose from 9.2% in 1998 to 11.1%. It was the Hartz reforms to the labor market, enacted between 2003 to 2005, plus other changes made as part of the “Agenda 2010” around that time that eventually turned Germany from the “sick man” of Europe into the “locomotive of growth” of the continent.Growth went from below the EU average to above…

…while unemployment went from above the EU average to below.

…while unemployment went from above the EU average to below.

As long as the CDU/CSU is in the coalition, these reforms are likely to be intact. They could even be enhanced if the FDP joins the coalition. However, a swing left in the government – e.g the “black/green/red” coalition of CDU/CSU with the Greens and the SPD, which have been the source of much of the pressure to ease up on the reforms, could put more burdens on employers that drive jobs abroad and lower Germany’s growth rate.

For more information: The German news channel DW has an extremely useful website on the German elections in which they discuss the issues and the players in English. Deutsche Bank also makes much of its research on Germany available on its website.

The German political system explained (briefly)

The Bundestag (“Federal Diet”) is the most important part of the legislative branch of the German federation. Together with the Bundesrat (see below), it comprises the legislative branch of the federal government. It passes laws, decides on the federal budget, exercises oversight of the executive branch, and decides on foreign activity by the armed forces.

It elects a Chancellor, who is responsible for forming a government by proposing candidates for the federal cabinet and determining policy guidelines (see below).

Electoral system: The electoral system is extraordinarily complicated. It’s a mixed-member proportional representation system.

Every elector has two votes: a constituency vote (first vote) and a party list vote (second vote). The first votes elect 299 members in single-member constituencies. This is done by first-past-the-post voting, i.e. the candidate who gets the most votes wins even if they don’t get a majority. The second votes are then used to allocate a proportionate number of seats to the parties. These are allocated first in the states and then on the federal level. There are then a whole lot of complicated ways in which the seats are reapportioned depending on whether each party wins fewer or more constituency seats in a state that its second votes would entitle it to. Anyone wanting more detail than that is welcome to read about it on Wikipedia. I wish you good luck.

Role of the chancellor: The chancellor is the head of government and the chief executive of Germany. The chancellor can appoint and dismiss members of the cabinet at will (technically the president does it on the recommendation of the chancellor). Article 65 of the Basic Law says “The Federal Chancellor shall determine and be responsible for the general guidelines of policy.” Chancellors have used this rule to take control over the cabinet, treating cabinet members as subordinates whose job it is to implement the chancellor’s views and making the chancellor the clear focus of power in Germany.

The Bundesrat (“Federal Council”) s the body that represents the country’s 16 Lander (states) at the federal level. The main difference from the Bundestag is that the representatives are appointed by the state governments, rather than being elected directly by the people. It has only 69 members and normally has one session a month to vote on legislation prepared in committee. Its main purpose is to defend the interests of the Lander with respect to the federal government and, indirectly, the EU. The legislative authority of the Bundesrat is subordinate to that of the Bundestag but still essential. The federal government must present all its legislative initiatives first to the Bundesrat; only thereafter can a proposal be passed to the Bundestag.

Constitutional changes require the approval of the majority of two-thirds of all votes in Bundestag and Bundesrat. This gives the Bundesrat an absolute veto against constitutional change. For other legislation the Bundesrat can use a conditional veto that the Bundestag can overrule if it has enough votes (50%+1 in some cases, two-thirds in others), or an absolute veto that requires a joint committee to work out a compromise.

The state governments are required to vote en bloc in the Bundesrat. If a state’s delegation can’t agree on how to vote, they abstain. This automatically counts as a “no” vote. If the opposition parties have enough representation in enough states, it enables them to veto legislation this way.

The German federal election will take place on Sep. 26th. This is the first such election in 16 years that won’t have Angela Merkel on the ballot. It will elect a new leader for Germany and in effect a new leader for the European Union. Will German policies change dramatically after 16 years under Merkel? As Germany is the pivotal economy in Europe, accounting for nearly 30% of Eurozone GDP, its future strongly influences the continent and the currency. In this piece I’d like to explore the likely winner(s) of the election and what they might mean for Europe and the world at large.

First off, what are the main issues facing Germany in this election, the issues that the parties differ on? The major ones are:

Immigration: A common refugee policy is the #1 concern for European policy among voters. Germany absorbs the largest number of refugees of any EU country. Most parties are in favor of sharing this burden more evenly among the member countries. On other aspects of refugee policy though there’s a clear left/right divide: left-wing parties emphasize the right to claim asylum while right-wing parties emphasize strong border control.

Climate change: The recent floods in Germany have brought home the importance of this issue for everyone’s day-to-day life. Under its Fit for 55 package, the EU has set itself a binding target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. This requires current greenhouse gas emission levels to drop substantially in the next decades....

First off, what are the main issues facing Germany in this election, the issues that the parties differ on? The major ones are:

Immigration: A common refugee policy is the #1 concern for European policy among voters. Germany absorbs the largest number of refugees of any EU country. Most parties are in favor of sharing this burden more evenly among the member countries. On other aspects of refugee policy though there’s a clear left/right divide: left-wing parties emphasize the right to claim asylum while right-wing parties emphasize strong border control.

Climate change: The recent floods in Germany have brought home the importance of this issue for everyone’s day-to-day life. Under its Fit for 55 package, the EU has set itself a binding target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. This requires current greenhouse gas emission levels to drop substantially in the next decades....

To continue reading the full report, please log in to your BDSwiss Dashboard

Not an existing member? Register an account in a few seconds, and gain unlimited access to exclusive research resources.

Access Leading Analysis, Market Briefs & Reports, Daily Live Webinars and much more!

您的资金会涉及风险

您的资金会涉及风险