Weekly Outlook

The punch bowl, the put, and now what?

In October 1955, Fed Chair William McChesney Martin, Jr. delivered a speech to the New York Group of the Investment Bankers Association of America. In that speech, Martin said that the job of the Fed was to prevent inflation, if necessary by taking unpopular steps. “In the field of monetary and credit policy, precautionary action to prevent inflationary excesses is bound to have some onerous effects…Those who have the task of making such policy don’t expect you to applaud. The Federal Reserve…is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” (emphasis added)

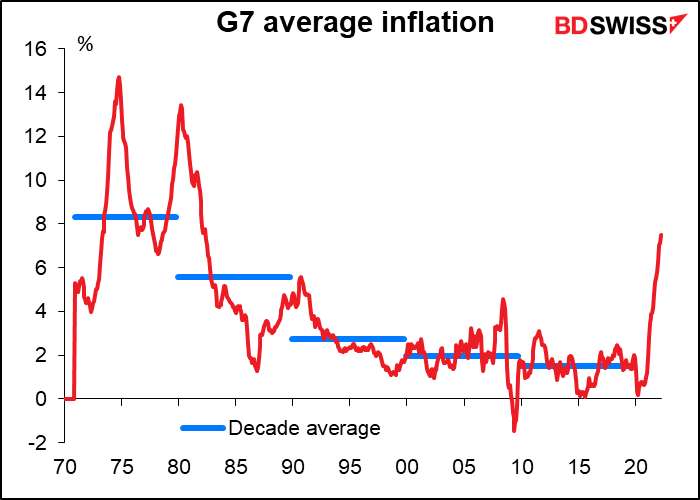

Years later, as inflation came down globally, the role of central banks changed. Since the “Great Moderation” began in the late 1980s, central banks have focused more on general macro-economic management than on containing inflation. Their role flipped: instead of removing the punch bowl, they saw considered it their responsibility to spike it when an economy’s “animal spirits” started to flag. The “Greenspan put,” by which it was assumed that the Fed would come to the rescue of the stock market whenever it began to fall, replaced the punch bowl.

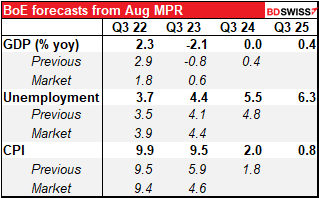

We’re now entering a third period. At this point, what central banks should do, or what they’re likely to do, isn’t entirely clear to the markets. This conundrum was most evident in Thursday’s Monetary Policy Report from the Bank of England, which contained their new forecasts. They’re pretty grim. The Bank is now forecasting out-of-control inflation along with a recession lasting some five quarters.

How well can we trust these forecasts? Well, let’s review their track record for a moment, focusing on their forecast for peak inflation:

- 21; “peaking at around 5% in April 22.”

- 22: “peaking at around 7.25% in April 22”

- May 22: “may rise to in excess of 10% towards the end of the year..”

- Aug: 22: “just over 13% in 2022 Q4.”

Not such a great track record, eh? This isn’t unique to the BoE though. I think every central bank – and a lot of private-sector forecasters, too – have been caught unawares. (I have to admit, I was firmly in “team transitory” as the pandemic wound down as I too thought everything would gradually go back to normal.)

That’s not the point, though. The point is what the Bank’s policy prescription is in this situation. Did it craft its policy to bolster growth or to fight inflation? The answer’s clear: It hiked rates by 50 bps, promised more to come in September, and announced it will start active “quantitative tightening” by selling bonds. It came down decisively on the side of fighting inflation.

The main theme in the market nowadays is the struggle to figure out how central banks will react – what their reaction function is, in economic terms — when confronted with the conflicting requirements of runaway inflation and flagging economies. The long period of moderate inflation has made people forget what the main task of central banks is. Investors are still counting on central banks to manage growth, not inflation. But that’s not what the central banks are saying they’ll do.

How reasonable is the market’s assumption? Let’s review the mandates of the major central banks:

Fed: “the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

European Central Bank (ECB): “The primary objective of the European System of Central Banks…shall be to maintain price stability.”

Bank of Japan: “In carrying out its monetary policy duties, the Bank shall contribute to the development of a sound national economy through the maintenance of price stability.”

Bank of England: “In relation to monetary policy, the objectives of the Bank of England shall be –

- To maintain price stability, and

- Subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty’s Government, including its objectives for growth and employment.”

Swiss National Bank: ‘It shall ensure price stability. In so doing, it shall take due account of economic developments.”

Bank of Canada: “to promote the economic and financial welfare of Canada.”

Reserve Bank of Australia:

(a) the stability of the currency of Australia;

(b) the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and

(c) the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand: “the goals of maintaining a stable general level of prices over the medium term and supporting maximum sustainable employment.”

In short, the main responsibility of most central banks is clear: they’re required to work for price stability, not growth. Several have employment as an additional goal. The Bank of Canada has an extraordinarily vague remit, but they interpret it as meaning “to keep inflation low, stable and predictable.”

The Bank of England as usual tried to emphasize this fact in its statement following the meeting: “The MPC’s remit is clear that the inflation target applies at all times, reflecting the primacy of price stability in the UK monetary policy framework.”

Several Fed speakers have also been emphasizing recently that they intend to “do whatever it takes” to get inflation back down to 2%. Minneapolis Fed President Kashkari, the #1 dove on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), said that the idea of the Fed cutting rates in 2023 seems like “a very unlikely scenario right now given what I know about the underlying inflation dynamics,” even though that’s exactly what the market is predicting. “Work on inflation is nowhere near almost done,” said San Francisco Fed President Daly (NV), “We have a long way to go on that task…We need to keep committed until we actually see it in the data” that inflation is materially coming down.

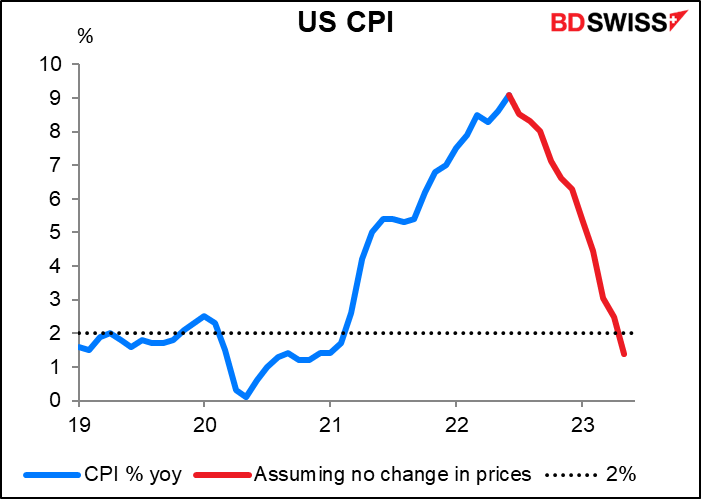

The fact is, even if prices don’t change at all in the US from now on, it wouldn’t be until next May that inflation came down to the Fed’s 2% target. And how likely is that to happen? Not very.

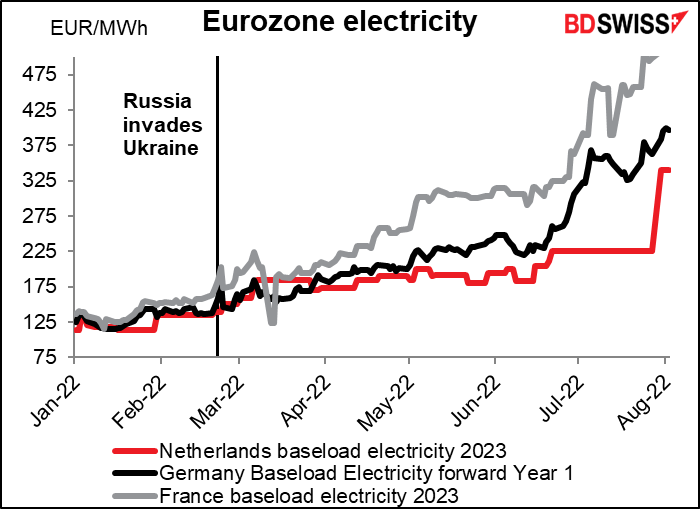

In Europe, look what markets are expecting electricity prices to be next year: 2x to 3x as much as they were at the beginning of this year.

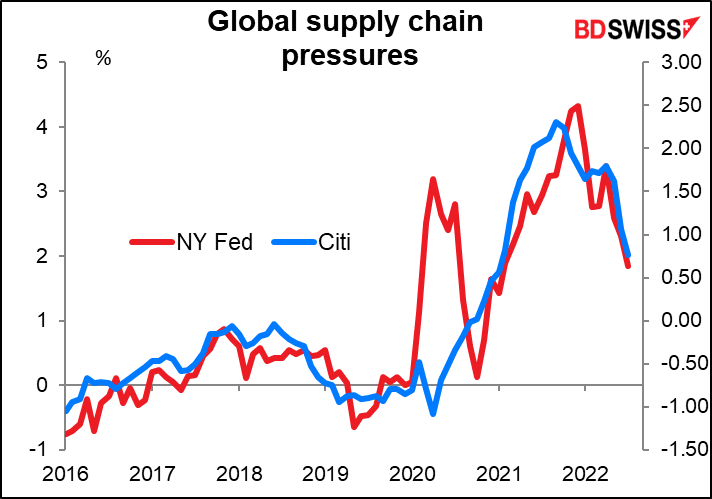

Globally, supply chain pressures are coming down but remain unusually high, indicating that the pandemic’s distortions persist.

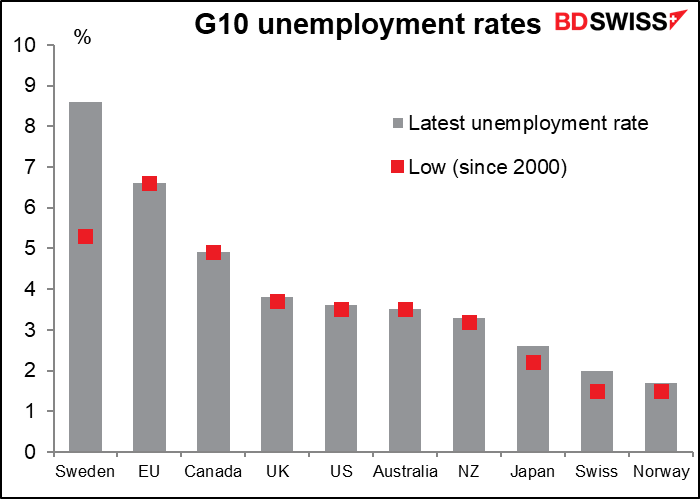

Nor is the fear of mass unemployment likely to constrain policy. For most of the G10 countries (Sweden being the only exception), unemployment is at or near the lowest level in 20 years or more. Central banks therefore believe they can hike rates without risking mass unemployment. “We are, in effect, saying that something unprecedented can occur because the labor market is in an unprecedented situation,” according to Fed Gov. Waller and another Fed economist.

To sum up: I think investors are underestimating the degree of tightening that central banks will need to do to get inflation under control. I think they are also underestimating the willingness of central bankers to take those steps.

Next week: Lots of inflation data including US CPI

The second week of the month is generally quiet in terms of indicators. The focus is always on the US consumer price index on Wednesday. There’s a host of other inflation data coming out, including producer prices for Japan, China, and the US. Finally, on Friday we’ll get the UK “short-term indicator day,” including this time the quarterly GDP figure for Q2.

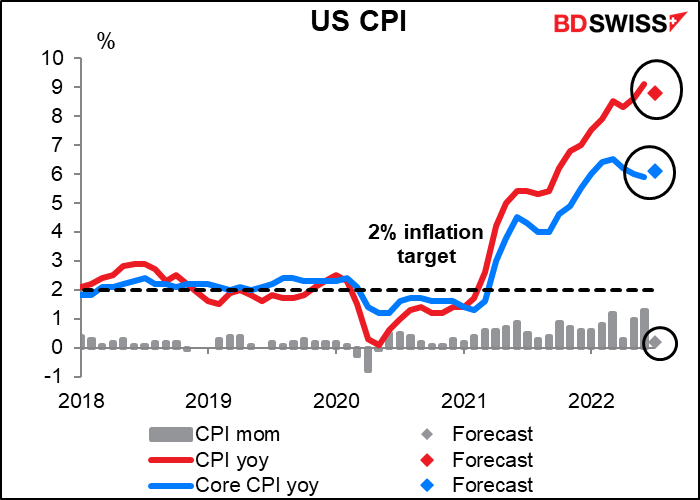

The light at the end of the tunnel? The headline US CPI is forecast to decline somewhat. Not a lot – to 8.8% yoy from 9.1% — but it may spark hopes that inflation has peaked. Core inflation though is forecast to rise a bit, although not back to where it was in March (6.5% yoy).

Alas, the data are open to interpretation. The market may perceive this as a turning point, but I doubt if the Committee will. That’s because if we take the forecast three-month change and annualize it, both the headline and the core rate are still going up – the core rate by quite a lot. The decline in the year-on-year rate of increase therefore has more to do with base effects (what was happening a year ago) than with what’s happening today. This may keep officials on their toes.

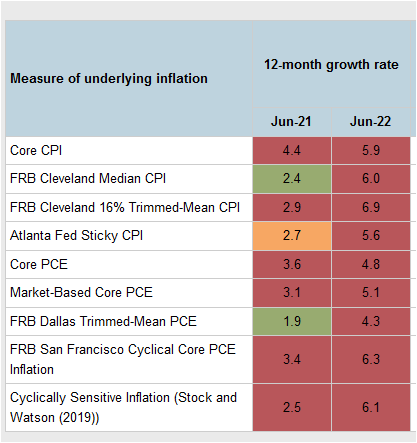

Indeed, if we look at the Atlanta Fed’s Underlying Inflation Dashboard, we can see that even the most optimistic measure of underlying inflation is more than twice as high as the Fed’s target. It’ll take some time for these figures to come down even if energy prices do moderate.

Other inflation data out from the US this coming week includes productivity and unit labor costs (Tue), producer prices (Wed), import prices (Thu), and the University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey (Fri), with its estimate of expected inflation. Fed officials specifically mentioned that survey as one of the factors that pushed them to hike rates by 75 bps in June rather than the widely expected 50 bps.

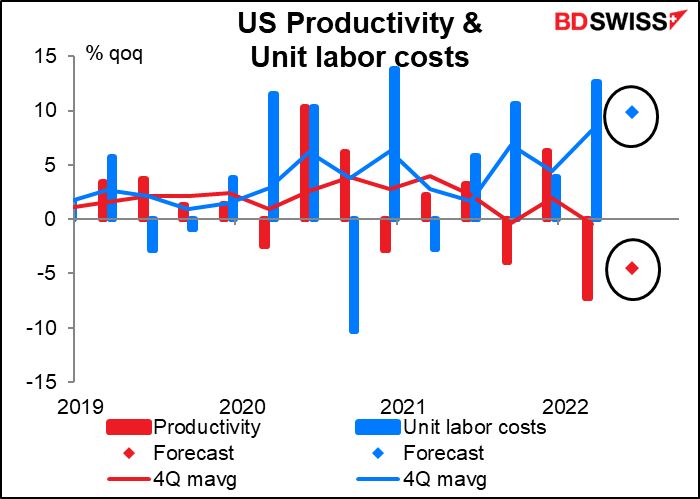

The productivity and unit labor cost data, while not that significant for the FX market, is forecast to be disturbing. The market expects to see falling productivity and rising unit labor costs. That’s a bad combination for companies and could hurt stock prices.

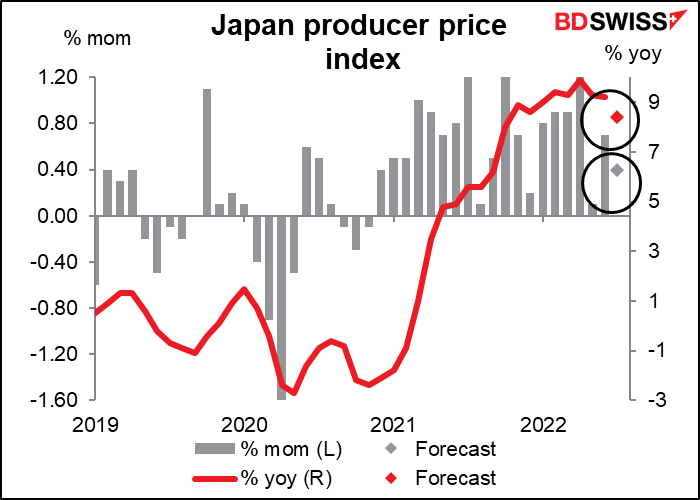

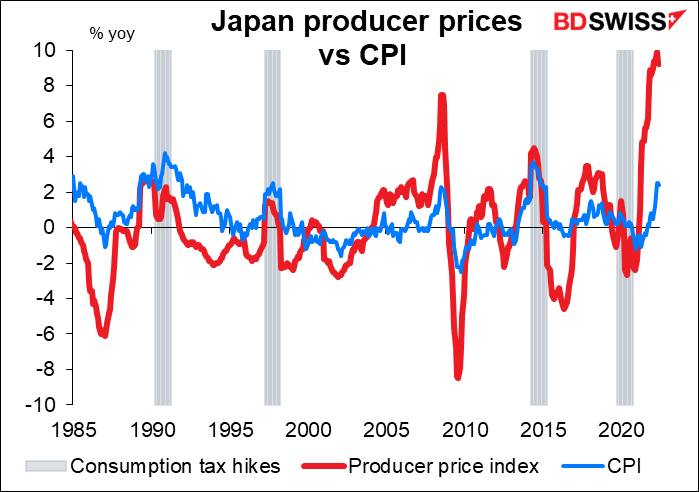

Japan releases its producer price index (PPI) on Wednesday. It’s expected to slow, but at 8.4% yoy remain far above the Bank of Japan’s 2% inflation target.

The relationship between the PPI and the CPI isn’t that close though. It’s not clear that even this elevated level of producer prices will be enough to pull up Japan’s staggeringly low consumer price inflation.

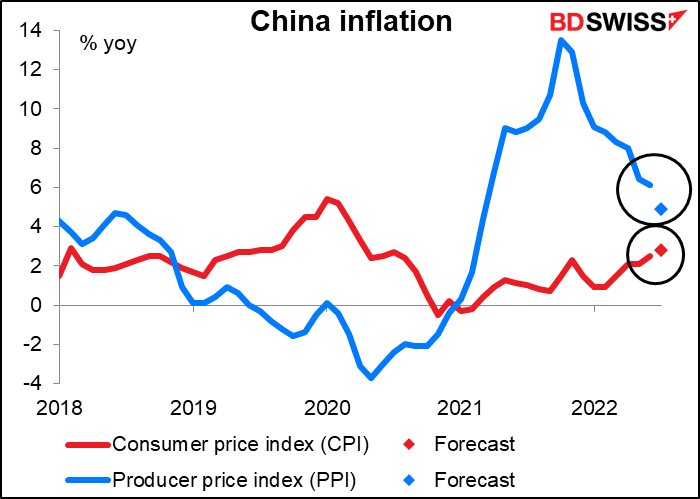

China also releases its PPI (and CPI) on Wednesday. The CPI is dominated by domestic food prices and so has little international implications. The PPI however is effectively China’s export prices, which in turn are many countries’ imported manufactured goods prices. It therefore is quite important internationally. And it’s expected to come down a lot. That’s a good sign for global inflation. It perhaps goes along with the decline shown above in global supply chain pressures, as many of those pressures originate in China.

Germany announces the final revision of July’s CPI on Wednesday. That’s about the only EU economic statistic of interest for the week.

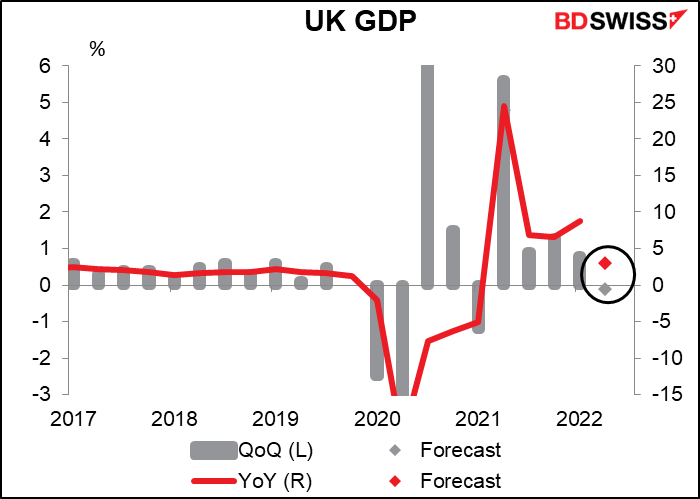

Finally, Friday is “short-term indicator day” for the UK. They’ll announce the monthly and quarterly GDP, industrial and manufacturing production, and the trade balance. As usual, the focus will be on the GDP figure.

The Q2 GDP figure is expected to show a small decline from the previous quarter but still be up year-on-year.

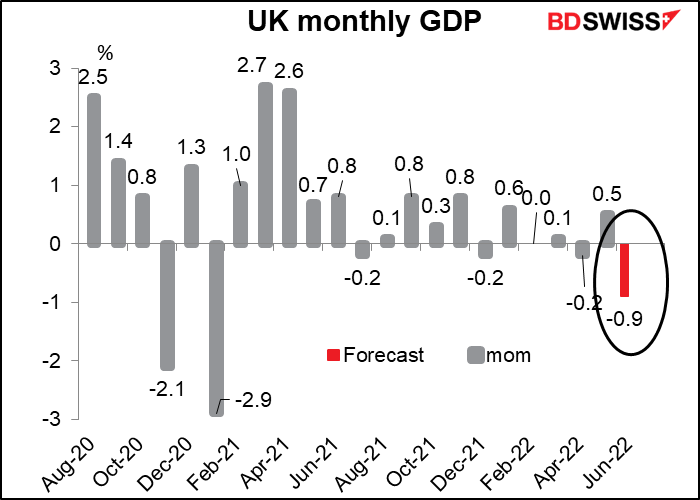

I think the more important figure though will be the monthly GDP figure for June. That will give a better feel for how badly the economy is imploding nowadays. It shows what kind of momentum the economy has going into Q3. According to Thursday’s Bank of England Monetary Policy Report, “GDP growth in the United Kingdom is slowing…The United Kingdom is now projected to enter recession from the fourth quarter of this year.” The monthly figure could give us a hint about whether the economy is on schedule to meet that target.

Industrial and manufacturing production are expected to corroborate the downturn. They’re both forecast to be -1.1% mom (which is why there’s only one dot visible in the chart).

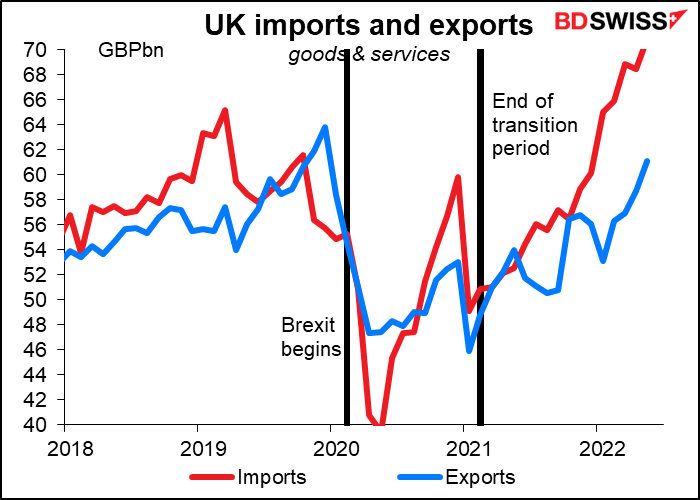

No forecasts are available yet for trade, but there’s little reason to expect any good news there. UK imports have hit record levels in recent months but exports have just barely recovered to the pre-Brexit level. The UK trade account, always the economy’s Achilles heel, seems to be headed for trouble.